-

Looking for HSC notes and resources? Check out our Notes & Resources page

Make a Difference – Donate to Bored of Studies!

Students helping students, join us in improving Bored of Studies by donating and supporting future students!

Chemistry Questions (1 Viewer)

- Thread starter Aysce

- Start date

Thief

!!

- Joined

- Dec 18, 2010

- Messages

- 561

- Gender

- Male

- HSC

- 2013

Re: Mole calculations

If there is one mole of AlCl3, then there is one mole of Al and 3 moles of ClI know it's a little late but I've been thinking, with your method aren't we only finding the number of moles of aluminium chloride? How are we actually finding the number of moles of aluminium?

Aysce

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jun 24, 2011

- Messages

- 2,393

- Gender

- Male

- HSC

- 2012

Re: Mole calculations

I just don't understand how you are able to attain the same answer for aluminium as if you were finding the number of moles of sodium chloride because:

Number of moles = Mass/Molar mass

= 0.374/133.5

= 2.80 x 10^-3 mol

Why is this the same for aluminium?

What I was asking was a little ambiguous - I didn't necessarily mean the actual number of Aluminium moles in the compound but how many Aluminium moles are in 0.374g of AlCl3 so yes I am referring to the mass.Actually i think i would just say its in a ratio of 1-3, because you need only 1 mole of al to 3 moles of cl but having said that are you referring specifically to the mass as well?

I just don't understand how you are able to attain the same answer for aluminium as if you were finding the number of moles of sodium chloride because:

Number of moles = Mass/Molar mass

= 0.374/133.5

= 2.80 x 10^-3 mol

Why is this the same for aluminium?

Last edited:

Re: Mole calculations

Gimme a sec. I'll offer some input

I'm fairly sure that it's not...What I was asking was a little ambiguous - I didn't necessarily mean the actual number of Aluminium moles in the compound but how many Aluminium moles are in 0.374g of AlCl3 so yes I am referring to the mass.

I just don't understand how you are able to attain the same answer for aluminium as if you were finding the number of moles of sodium chloride because:

Number of moles = Mass/Molar mass

= 0.374/133.5

= 2.80 x 10^-3 mol

Why is this the same for aluminium?

Gimme a sec. I'll offer some input

Sy123

This too shall pass

- Joined

- Nov 6, 2011

- Messages

- 3,725

- Gender

- Male

- HSC

- 2013

Re: Mole calculations

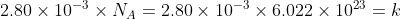

Find the number of moles in AlCl3

2.80 x 10^-3

By definition of a mole, one mole has the avagadro's constant amount of particles in it.

Hence the number of molecules of AlCl3

How many atoms of Al is there? Well for every one molecule of AlCl3, there is 1 Al atom, hence there are the same number of AlCl3 molecules as there are Al atoms.

Likewise there are 3 times as many Cl atoms as AlCl3 molecules

Hence there are k Al atoms in AlCl3, (3k for Cl)

Divide by Avogadro's constant again to obtain the number of moles. This is why there are the same amount of moles of Al and AlCl3. (which is what I think you were asking?)

From what I interpreted from the question:What I was asking was a little ambiguous - I didn't necessarily mean the actual number of Aluminium moles in the compound but how many Aluminium moles are in 0.374g of AlCl3 so yes I am referring to the mass.

I just don't understand how you are able to attain the same answer for aluminium as if you were finding the number of moles of sodium chloride because:

Number of moles = Mass/Molar mass

= 0.374/133.5

= 2.80 x 10^-3 mol

Why is this the same for aluminium?

Find the number of moles in AlCl3

2.80 x 10^-3

By definition of a mole, one mole has the avagadro's constant amount of particles in it.

Hence the number of molecules of AlCl3

How many atoms of Al is there? Well for every one molecule of AlCl3, there is 1 Al atom, hence there are the same number of AlCl3 molecules as there are Al atoms.

Likewise there are 3 times as many Cl atoms as AlCl3 molecules

Hence there are k Al atoms in AlCl3, (3k for Cl)

Divide by Avogadro's constant again to obtain the number of moles. This is why there are the same amount of moles of Al and AlCl3. (which is what I think you were asking?)

Aysce

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jun 24, 2011

- Messages

- 2,393

- Gender

- Male

- HSC

- 2012

Re: Mole calculations

You're answering what I was asking but I hoped for a simpler way (I understand it though) - Much like someth1ng's method. I don't know how he knew what particular values to choose to attain the number of moles of aluminium. He just plugged in the mass and molar mass of AlCl3 but it doesn't make sense to me :/

Do you mean how there is 1 AlCl3 molecule and 1 Al atom or that they have the same number of molecules and atoms?From what I interpreted from the question:

Find the number of moles in AlCl3

2.80 x 10^-3

By definition of a mole, one mole has the avagadro's constant amount of particles in it.

Hence the number of molecules of AlCl3

How many atoms of Al is there? Well for every one molecule of AlCl3, there is 1 Al atom, hence there are the same number of AlCl3 molecules as there are Al atoms.

Likewise there are 3 times as many Cl atoms as AlCl3 molecules

Hence there are k Al atoms in AlCl3, (3k for Cl)

Divide by Avogadro's constant again to obtain the number of moles. This is why there are the same amount of moles of Al and AlCl3. (which is what I think you were asking?)

You're answering what I was asking but I hoped for a simpler way (I understand it though) - Much like someth1ng's method. I don't know how he knew what particular values to choose to attain the number of moles of aluminium. He just plugged in the mass and molar mass of AlCl3 but it doesn't make sense to me :/

Last edited:

Sy123

This too shall pass

- Joined

- Nov 6, 2011

- Messages

- 3,725

- Gender

- Male

- HSC

- 2013

Re: Mole calculations

What someth1ng is doing is that he is using the very definition of what a mole is:

if n is the number of moles, and Mw is the MOLAR mass.

And m is the mass.

By definition the unit of n is mol

In order to transform mol into g

What measurement uses g/mol?

That is the definition of molar mass

The amount of grams per mole of a substance. Hence we multiply together to get the mass.

Basically a proof of the formula:

As for a way to get the answer without the formula or the formula logic I do not know of a way, unless there is some long agonizing unnecessary way of utilising the proper definition of mole being the number of particles in 12 grams of pure Carbon-12 isotope, and then somehow comparing Carbon-12 to AlCl3 maybe?

In our given amount of substance, in this substance if there is an 'n' number of AlCl3 molecules, since there is only 1 Al atom for every 1 AlCl3 molecule because this Al atom is PART of the AlCl3 molecule itself, therefore there must be an 'n' number of Al atoms.Do you mean how there is 1 AlCl3 molecule and 1 Al atom or that they have the same number of molecules and atoms?

You're answering what I was asking but I hoped for a simpler way (I understand it though) - Much like someth1ng's method. I don't know how he knew what particular values to choose to attain the number of moles of aluminium. He just plugged in the mass and molar mass of AlCl3 but it doesn't make sense to me :/

What someth1ng is doing is that he is using the very definition of what a mole is:

if n is the number of moles, and Mw is the MOLAR mass.

And m is the mass.

By definition the unit of n is mol

In order to transform mol into g

What measurement uses g/mol?

That is the definition of molar mass

The amount of grams per mole of a substance. Hence we multiply together to get the mass.

Basically a proof of the formula:

As for a way to get the answer without the formula or the formula logic I do not know of a way, unless there is some long agonizing unnecessary way of utilising the proper definition of mole being the number of particles in 12 grams of pure Carbon-12 isotope, and then somehow comparing Carbon-12 to AlCl3 maybe?

yasminee96

Active Member

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2012

- Messages

- 346

- Gender

- Female

- HSC

- 2013

Re: Mole calculations

there's 0.374g of AlCl3, convert that into moles (in this case there is no option but to use the formula n=m/mw, unless ur crazy haha)

now if u look at the ratio of Al:Cl, it's 1:3 ; so basically in every 1 mol of aluminium chloride, there's one mole of aluminium, 3 moles of chlorine, right?

so if we find that there are 2.8 x 10^-3 moles of AlCl3 in 0.374 g, then there are also 2.8 x 10^-3 moles of aluminium and (2.8 x 10^-3) x 3 moles of chlorine

but, of course, you're only asking for moles aluminium so the answer should be 2.8 x 10^-3 due to the mole ratios in the actual empirical formula of aluminium chloride

KEEP IN MIND: this should only work if the formula is an empirical formula.

this is what i would do, however i'm also just a student and could be wrong, don't judge me haha

there's 0.374g of AlCl3, convert that into moles (in this case there is no option but to use the formula n=m/mw, unless ur crazy haha)

now if u look at the ratio of Al:Cl, it's 1:3 ; so basically in every 1 mol of aluminium chloride, there's one mole of aluminium, 3 moles of chlorine, right?

so if we find that there are 2.8 x 10^-3 moles of AlCl3 in 0.374 g, then there are also 2.8 x 10^-3 moles of aluminium and (2.8 x 10^-3) x 3 moles of chlorine

but, of course, you're only asking for moles aluminium so the answer should be 2.8 x 10^-3 due to the mole ratios in the actual empirical formula of aluminium chloride

KEEP IN MIND: this should only work if the formula is an empirical formula.

this is what i would do, however i'm also just a student and could be wrong, don't judge me haha

Aysce

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jun 24, 2011

- Messages

- 2,393

- Gender

- Male

- HSC

- 2012

Re: Mole calculations

What you're doing make sense and I understand. Would this method be legit though? (im new to this)there's 0.374g of AlCl3, convert that into moles (in this case there is no option but to use the formula n=m/mw, unless ur crazy haha)

now if u look at the ratio of Al:Cl, it's 1:3 ; so basically in every 1 mol of aluminium chloride, there's one mole of aluminium, 3 moles of chlorine, right?

so if we find that there are 2.8 x 10^-3 moles of AlCl3 in 0.374 g, then there are also 2.8 x 10^-3 moles of aluminium and (2.8 x 10^-3) x 3 moles of chlorine

but, of course, you're only asking for moles aluminium so the answer should be 2.8 x 10^-3 due to the mole ratios in the actual empirical formula of aluminium chloride

KEEP IN MIND: this should only work if the formula is an empirical formula.

this is what i would do, however i'm also just a student and could be wrong, don't judge me haha

yasminee96

Active Member

- Joined

- Sep 8, 2012

- Messages

- 346

- Gender

- Female

- HSC

- 2013

Re: Mole calculations

well that's what i was taught my teacher went ahead and taught us all of this in prelim instead of the metals chapter because he thought it was stupid hahaha, and yeh if i came across a question like that, that's exactly how i would answer it, because that is what was taught to me and it makes sense to me !

my teacher went ahead and taught us all of this in prelim instead of the metals chapter because he thought it was stupid hahaha, and yeh if i came across a question like that, that's exactly how i would answer it, because that is what was taught to me and it makes sense to me !

keep in mind though, the ratio is for moles

well that's what i was taught

keep in mind though, the ratio is for moles

Riproot

Addiction Psychiatrist

- Joined

- Nov 10, 2009

- Messages

- 8,227

- Gender

- Male

- HSC

- 2011

- Uni Grad

- 2017

Because the repulsive forces of the metal atoms is bigger duh.

Kurosaki

True Fail Kid

Re: Why does metallic bonding become weaker when atoms increase in size?

He means that larger atoms have more electrons, so the metal cations formed by metallic bonding thus form stronger charged ions, and thus reject each ther more strongly I think? Something like that I'm sure

He means that larger atoms have more electrons, so the metal cations formed by metallic bonding thus form stronger charged ions, and thus reject each ther more strongly I think? Something like that I'm sure

Aysce

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jun 24, 2011

- Messages

- 2,393

- Gender

- Male

- HSC

- 2012

Re: Why does metallic bonding become weaker when atoms increase in size?

Looking more for an answer like this. Makes sense, thanksHe means that larger atoms have more electrons, so the metal cations formed by metallic bonding thus form stronger charged ions, and thus reject each ther more strongly I think? Something like that I'm sure

Kurosaki

True Fail Kid

Re: Why does metallic bonding become weaker when atoms increase in size?

No worries bro

No worries bro

Riproot

Addiction Psychiatrist

- Joined

- Nov 10, 2009

- Messages

- 8,227

- Gender

- Male

- HSC

- 2011

- Uni Grad

- 2017

ftfyHe means that larger atoms have more electrons, so the metal cations formed by metallic bonding thus form stronger charged ions, and thus reject each ther more strongly I think? Something like that I'm sure, DUH!

Obvious

Active Member

- Joined

- Mar 22, 2010

- Messages

- 735

- Gender

- Male

- HSC

- 2013

- Uni Grad

- 2016

Re: Why does metallic bonding become weaker when atoms increase in size?

I really wouldn't bother taking this further unless you plan on learning some quantum chemistry beforehand. A truly valid answer would likely involve a lot of this, solid-state chemistry and who knows what else.

Edit: I have no idea how the first point correlates with position on the periodic table. The second and third characteristics are tied up with the first so that's a bit of a dead end as well.

http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Theoretical_Chemistry/Chemical_Bonding/Metalic_BondingBonding Characteristics

The strength of a metallic bond depends on three things:

1) The number of electrons that become delocalized from the metal

2) The charge of the cation (metal).

3) The size of the cation.

A strong metallic bond will be the result of more delocalized electrons, which causes the effective nuclear charge on electrons on the cation to increase, in effect making the size of the cation smaller. Metallic bonds are strong and require a great deal of energy to break, and therefore metals have high melting and boiling points.

A metallic bonding theory must explain how so much bonding can occur with such few electrons (since metals are located on the left side of the periodic table and do not have many electrons in their valence shells). The theory must also account for all of a metal's unique chemical and physical properties.

I really wouldn't bother taking this further unless you plan on learning some quantum chemistry beforehand. A truly valid answer would likely involve a lot of this, solid-state chemistry and who knows what else.

Edit: I have no idea how the first point correlates with position on the periodic table. The second and third characteristics are tied up with the first so that's a bit of a dead end as well.

Last edited:

Aysce

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jun 24, 2011

- Messages

- 2,393

- Gender

- Male

- HSC

- 2012

Re: Why does metallic bonding become weaker when atoms increase in size?

I'll check the link out soon.

I'll check the link out soon.

Haha nah, I think it's fine atm, not really worth looking further into. Thanks for your contributionhttp://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Theoretical_Chemistry/Chemical_Bonding/Metalic_Bonding

I really wouldn't bother taking this further unless you plan on learning some quantum chemistry beforehand. A truly valid answer would likely involve a lot of this, solid-state chemistry and who knows what else.

Edit: I have no idea how the first point correlates with position on the periodic table. The second and third characteristics are tied up with the first so that's a bit of a dead end as well.